International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 31, Issue 2, March 2019, Pages 159–163

In Part 2 of this two-part contribution made on behalf of the Innovation and Systems Change Working Group of the International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua), we continue the argument for refashioning health systems in response to ageing and other pressures. Massive ageing in many countries and accompanying technological, fiscal and systems changes are causing the tectonic plates of healthcare to shift in ways not yet fully appreciated.

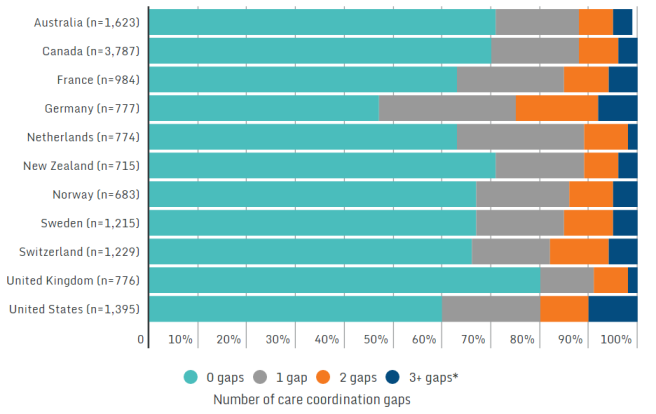

In response, while things remain uncertain, we nevertheless have to find ways to proceed. We propose a strategy for stakeholders to pursue, of key importance and relevance to the ISQua: to harness flexible standards and external assessment in support of needed change. Depending on how they are used, healthcare standards and accreditation can promote, or hinder, the changes needed to create better healthcare for all in the future. Standards should support people’s care needs across the life cycle, including prevention and health promotion. New standards that emphasise better coordination of care, those that address the entire healthcare journey and standards that reflect and predict technological changes and support new models of care can play a part. To take advantage of these opportunities, governance bodies, external assessment agencies and other authorities will need to be less prescriptive and better at developing more flexible standards that apply to the entire health journey, incorporating new definitions of excellence and acceptability. The ISQua welcomes playing a leadership role.